Its large domestic market stayed buoyant in the face of crashing world prices, but will not do so for much longer.

A major exporter, yet domestically oriented and self-contained, America's avoided most of the past year's global dairy market deflation. While Global Dairy Trade reports that Oceania's prices for various dairy powders have fallen anywhere from 31% to 45%, the first three quarters were kind to US dairy farms: September saw US dairy prices set new records. It share of world milk output increased from its usual 15% to 17% over this time too.

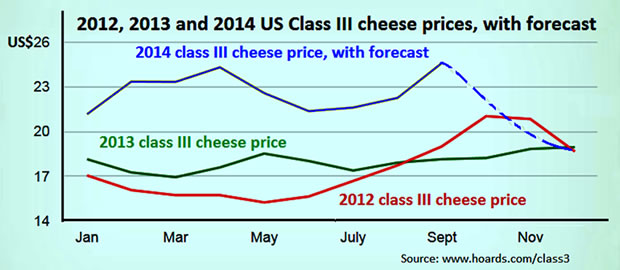

With dairy export prices suffering their biggest rout of the century, US class II dairy futures increased 25% since the start of 2014. In mid-2014, the retail price of American milk was 5.7% higher than a year earlier. But the good times are ending even as we speak.

On one hand, record high feed costs and strong export demand pushed US dairy prices up along with those in the rest of the world in the years 2011 to 2013. On the other hand, late 2014 saw US milk production stay flat.

According to Rabobank Food & Agribusiness Advisory Q3 Dairy Quarterly, "The lack of supply growth earlier in the year, and a surge in export sales left the market relatively short of cheese and butter –underpinning domestic prices for these commodities (and hence milk) well above F.O.B. Oceania levels."

This occurred just as China embarked on an early first quarter buying binge –and thereafter slashed procurement volumes for the rest of 2014. China's final dairy import binge occurred at the turn of the year, when a southern hemisphere drought had curtailed dairy powder supplies from Australia and New Zealand.

For a brief window of time, America became the dairy supplier of final resort. As a result, dairy export volumes in the first half of 2014 expanded 18% from a year earlier. This more than made up for a slack domestic market, where historically high dairy prices held back consumption growth. All this kept American dairy prices firm at a time when the world export market was enduring a sharp, acute downturn.

Moreover, once the unusually cold winter stopped disrupting output, with feed costs falling by more 40% and domestic dairy prices staying firm, profit margins widened considerably. As mid-year approached, a significant proportion of US dairy farms had also finished the repayment of short-term debts. Amid steadily widening profit margins, this gave them more net equity and greater confidence to expand their cow herds.

Moreover, once the unusually cold winter stopped disrupting output, with feed costs falling by more 40% and domestic dairy prices staying firm, profit margins widened considerably. As mid-year approached, a significant proportion of US dairy farms had also finished the repayment of short-term debts. Amid steadily widening profit margins, this gave them more net equity and greater confidence to expand their cow herds.

This encouraged a strong second and third quarter supply-side response. Even in drought stricken, major producing state like California, plunging feed costs more than compensated for the lack of available pastureland.

The accelerating supply-side response can be seen in USDA statistics: From near flat production in early 2014, US fluid milk output ran 2.4% of 2013's pace from May to July - but was 4% ahead of the previous year's monthly production in July itself.

The strong, mid-year supply side response has upset US dairy production forecasts. The USDA for example, forecasted a 1.8% increase in fluid milk output, which would have roughly kept pace with US population growth (assuming relatively flat per capita consumption).

On the other hand, Rabobank believes that US dairy producers' aggressive, mid-year attempt to capitalize on high domestic prices will result in output growing at least 3.5% in the second half of this year. When this is added to a roughly 1% increase in dairy production in the first half of the year (mostly coming in the second quarter), it implies that America's fluid milk output should rise approximately 2.5% to 3.0%.

With high US dairy prices attracting competition from imports and the world export market having endured a six month free-fall, this is not good news for America's dairy producers. Especially with Russia's ban on western dairy exports more than compensating for any bottoming out of the downturn in Chinese demand.

Even as cheaper imports take some US market share and start deflating domestic prices, surplus American dairy powders must compete on a depressed world market with surging Australian and New Zealand supplies. Having rebounded from last year's South Pacific drought, the latter's output is cresting towards a particularly strong seasonal fourth quarter peak.

The deflationary implications of these trends can already be seen in the US CME dairy futures: Although they increased 25% in the first nine months of this year, by late September, March class III milk futures due in March 2015 were trading some 25% below the level of those expiring in late October.

Of course, US dairy farmers can read the market signals of futures prices as well as anyone else. That implies that barring an unusually strong American economic growth, with domestic expansion highly limited scope and a dreary world market ahead of them, they are likely to curtail their production going into next year.

With production flattening out amid very limited potential for domestic consumption growth and plunging exports, the current, sharp increase in dairy product inventories will be curtailed and top out by the second quarter of next year.