June 10, 2014

An Asia driven Australian dairy revival?

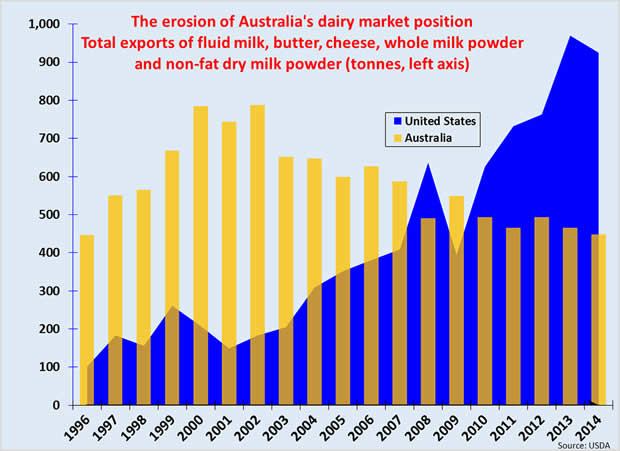

Trade liberalization, improving weather, export-oriented investments promise better days ahead but much market share has been lost to the United States.

by Eric J. BROOKS

An eFeedLink Hot Topic

With regular rainfall returning to Australia's southeast, dairy cattle inventories, cow productivity and milk output are all rising -but exports are lagging. 2013's output, estimated at 9.4 million liters by the USDA is expected to increase 5.3%, to 9.90 million litres in 2014.

Output, exports far below their peak

But this increase must be put into perspective: It remains 14.7% below the peak volume of 11.6 million litres set in 2002, even though both Australia's population and the world dairy market have grown significantly over the last 12 years. In sum, ten years of flat production and population growth have left less milk available for dairy exports, compromising the country's position on the world market.

On one hand, two years of historically high dairy export prices, a pastureland recovery and falling feed costs have enabled a mild rebound in cattle numbers. Although below their 1.9 million secular peak of the mid-2000s, the USDA estimates that dairy cattle numbers have recovered from their 2011 bottom of 1.6 million head and are expected to rise 6.2%, to 1.7 million head this year.

Cow productivity is increasing, rising 10% in the ten years to 2014, with the USDA attributing this to, "improved herd genetics, technology innovations and advances in pasture management." Especially in the large scale farms found in Australia's northeast and southwest, "unmanned aerial vehicles provide precision maps of their soil and water resources", enabling, "targeted use of inputs such as grain feed, irrigated water and fertilisers."

On the other hand, at 5,525 liters/year per cow, productivity is only about 50% to 60% the levels found in America and Europe -but this productivity deficit only creates problems when dry weather undermines the industry's pasture land base. Productivity is also challenged by the fact that Australia has three separate dairy business models, divided by climate and geography.

Three dairy industry models in one country

Rainy Victoria, South Australia and Tasmania account for approximately 75% to 80% of fluid milk production in any given year, are export-oriented and rely mostly on pastureland. These temperate areas are characterized by intensive grazing of pastureland blessed with nutrient rich grass. Tasmania in particular, has a climate-based, grassland dairy model very similar to that of New Zealand.

Southeast Australia's dairy industry intensification can be seen in Victoria, where the USDA estimates that in 2013, the average dairy farm had 330 head, well above the national average of 258 head. With its low input costs, milk from Australia's southeastern coast ends up on the world market, with dairy processing facilities in Victoria and South Australia accounting for 85% of export volume.

Victoria on its own accounts for 60% to 65% of Australian fluid milk output in any given year. With more northern regions afflicted by drought at the time, the Australian Dairy Board states that in 2012, Victoria accounted for 65.5% of Australia's fluid milk output, with Tasmania and South Australia contributing 8.3% and 3.6% respectively.

By comparison, the east coast of Queensland and New South Wales has tropical to sub-tropical climates, with poor soils and nutrient poor grasses. To make up for a lack of pastureland nutrients, northeastern Australian farms are larger in scale but with fewer cows per acre. With the last decade's dry spells badly impacting this region's shaky pastureland base, many farmers could not cope with high feed costs and much consolidation occurred within this region. In Queensland for example, the USDA estimates that the number of dairy cattle farms fell from 1,500 in 2000 to fewer than 500 today.

By comparison, the east coast of Queensland and New South Wales has tropical to sub-tropical climates, with poor soils and nutrient poor grasses. To make up for a lack of pastureland nutrients, northeastern Australian farms are larger in scale but with fewer cows per acre. With the last decade's dry spells badly impacting this region's shaky pastureland base, many farmers could not cope with high feed costs and much consolidation occurred within this region. In Queensland for example, the USDA estimates that the number of dairy cattle farms fell from 1,500 in 2000 to fewer than 500 today. With their less reliable input base, Australia's northeaster coast accounts for a far smaller share of the nation's milk. New South Wales accounted for 11.5% of output, with Queensland contributing another 5.1%

On the other side of the country, arid Western Australia's coast has sparse grassland and a dry feed dependent dairy sector similar to that of the American state of California. However, whereas California accounts for a large proportion of US output, Western Australia's limited arable land limited it to 3.6% of national fluid milk production. With their less competitive feed fundamentals, Australia's northeastern and southwestern coasts mostly serve the domestic market, accounting for 20% to 25% of fluid milk output any given year.

However, with long dry spells afflicting regions that supplied the domestic market, Australia's ability to take advantage of the world market has declined.

Long fall in exports over?

A long drought spanning the mid to late 2000s devastated Australia's supply of pasture land at a time of high feed prices, holding back production for a decade and resulting in lost export opportunities. For example, at 90,000 tonnes, whole milk powder (WMP) exports are 57.8% below their 2003 peak of 213,000 tonnes. Similarly non-fat dry milk powder (NFDM) exports of 140,000 tonnes remain 45.1% below their 2000 peak of 255,000 tonnes.

But better days are ahead. Along with larger cattle inventories, improving cattle productivity and favourable weather, Australia recently liberalized its dairy trade with large Asian markets. In April, Japan agreed to increase its duty-free Australian cheese import quota by 20,000 tonnes.

It also ruled that Australian cheese imported tariff-free under the quota need not be blended with higher-cost Japanese made cheese, which should boost its competitive position. Japan also reduced by 20% its tariffs on Australia's blue cheese and abolished its tariffs on milk protein concentrates and lactose, while reducing the tariff on yogurt from 14.9% to 7.45%.

It follows the dairy import liberalization it will enjoy with South Korea, after concluding a free trade agreement with that nation late last year.

Going forward, Australia is also working very hard to overcome a serious marketing hurdle in Asia's largest dairy market, China. Due to the 1998 free trade agreement between New Zealand and China, Australia's dairy products suffer a huge, tariff-induced price disadvantage. Although Australia hopes to finalize a comprehensive dairy trade liberalization agreement with China this year, some concessions have already been made –and attracted investment.

Export-oriented investment

For example, in April, China agreed to allow dairy co-operatives such as Norco to send fresh fluid milk to China within seven days rather than the 14 to 21 days previously required.

With China's demand for milk growing voraciously and the industry appearing to have reached a secular bottom, a new round of large capital investments is underway. With Australia's domestic dairy demand rising at a 1% annual pace, these expansions were export-oriented.

For example, April saw Murray Goulburn, Australia's leading dairy producer, announce it would put A$130 million (US$121.5 million) into constructing new cheese and infant formula making plants in Victoria and Tasmania. Six months earlier, it had put A$120 million (US$112.5 million) to expand its fluid milk processing facilities in Sydney and Melbourne. Moreover, Murray Goulburn recently applied to the Australian Securities Commission for permission to sell A$500 million (US$467.3 million) to expand and upgrade its dairy supply chain infrastructure –with Australia's own dairy market growing very slowly, only anticipated export demand could justify such a large capital investment.

Similarly, China's liberalization of fluid milk exports has motivated several companies to establish new UHT milk processing facilities for export either to China itself or Southeast Asia. For example, Pactum Group recently commissioned a new A$45 million (US$42.1 million) UHT processing facility, which it will use to supply milk-based beverages to China's Bright Dairy. Located in the town of Shepparton, Victoria, the plant's initial annual capacity of 100 million liters can be expanded to 300 million litres so as to grow in tandem with Asian dairy demand.

Similarly, Mondelez (formerly Kraft) is investing A$66 million (US$61.7 million) to expand its Hobart, Tasmania chocolate plant's annual capacity to 70,000 tonnes.

The potential of Australia's dairy industry is also being recognized by foreign investors. This year, Canada's Saputo acquired leading Victorian dairy processor WCB for A$600 million (US$560.7 million) French-owned Parmalet acquire Harvey Fresh for A$120 million (US$112.2 million). Previously, late 2013 saw New Zealand's Fonterra buy up Tasmania-based yogurt maker Tamar Valley while a group of Hong Kong-based investors acquired Victoria-based United Dairy Power for A$70 million (US$65.4 million).

Can it fully recover?

All this reflects the fact that among large dairy exporters, Australia may have the greatest potential for export-driven expansion. Nevertheless, after ten miserable years of drought and high feed costs when Australia lost its second place ranking in some key dairy lines to the United States, it has a long way to go to fulfil its potential.

It not only lost its ranking in some key export lines to the United States: At a time when the world dairy market has enjoyed a decade of aggressive expansion, Australia exports 35% less dairy products today by volume than it did in the early 2000s. Although its ideal geographic proximity to Asia and recent trade deals put it in a good market position, much depends on the weather.

Should regular precipitation resume for an extended period of years, it could easily expand its export and transcend the peak volumes achieved more than ten years ago. However, if drought occurs, high feed costs could put its exports at a disadvantage to those of the United States, which has superior productivity when Australia's cows cannot depend on pastureland. Consequently, while market opening trade liberalizations guarantee that exports will turn up after this year, Australia's capacity to recapture its previous larger share of the world dairy market requires an extended period of grass-friendly weather.

All rights reserved. No part of the report may be reproduced without permission from eFeedLink.